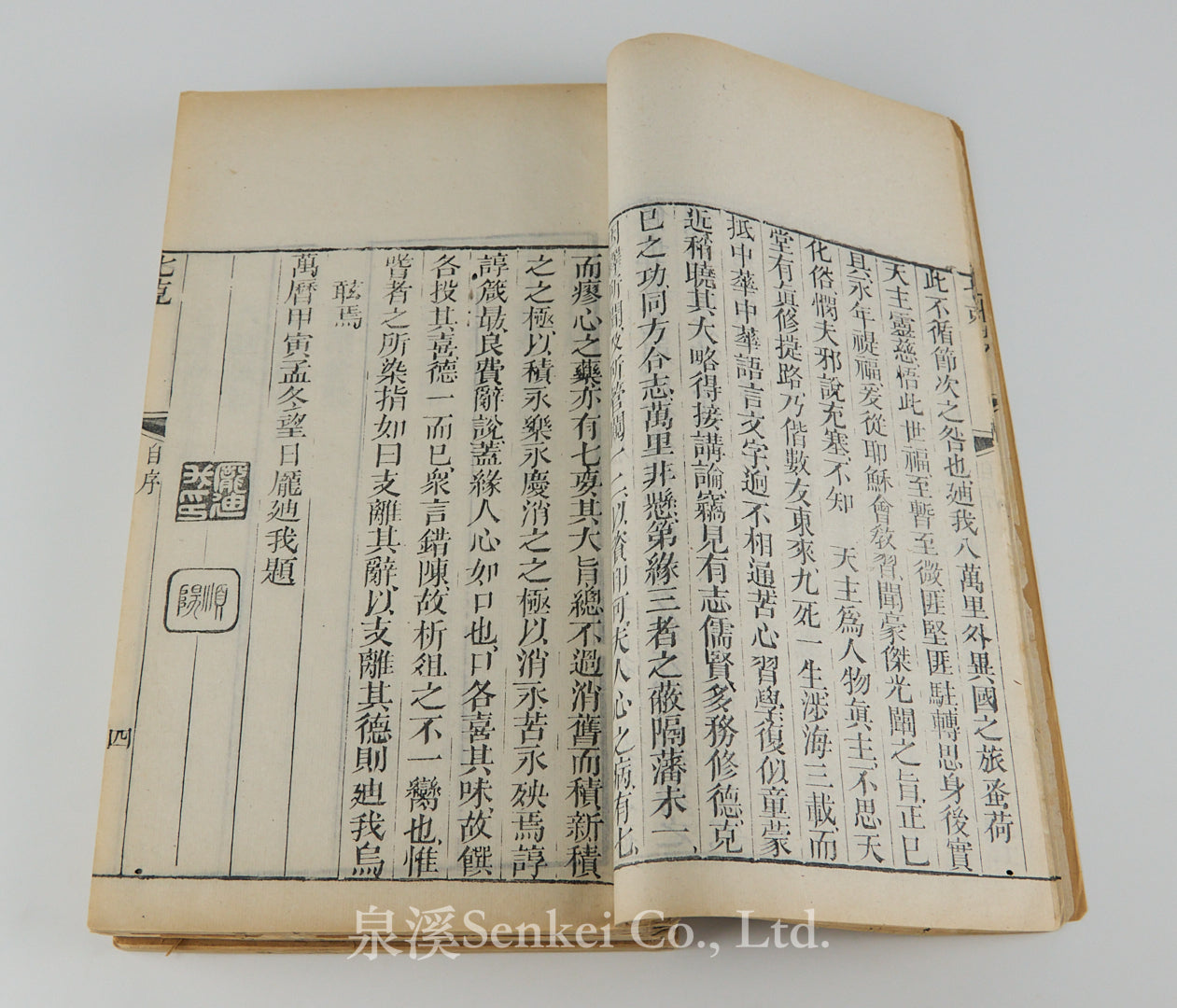

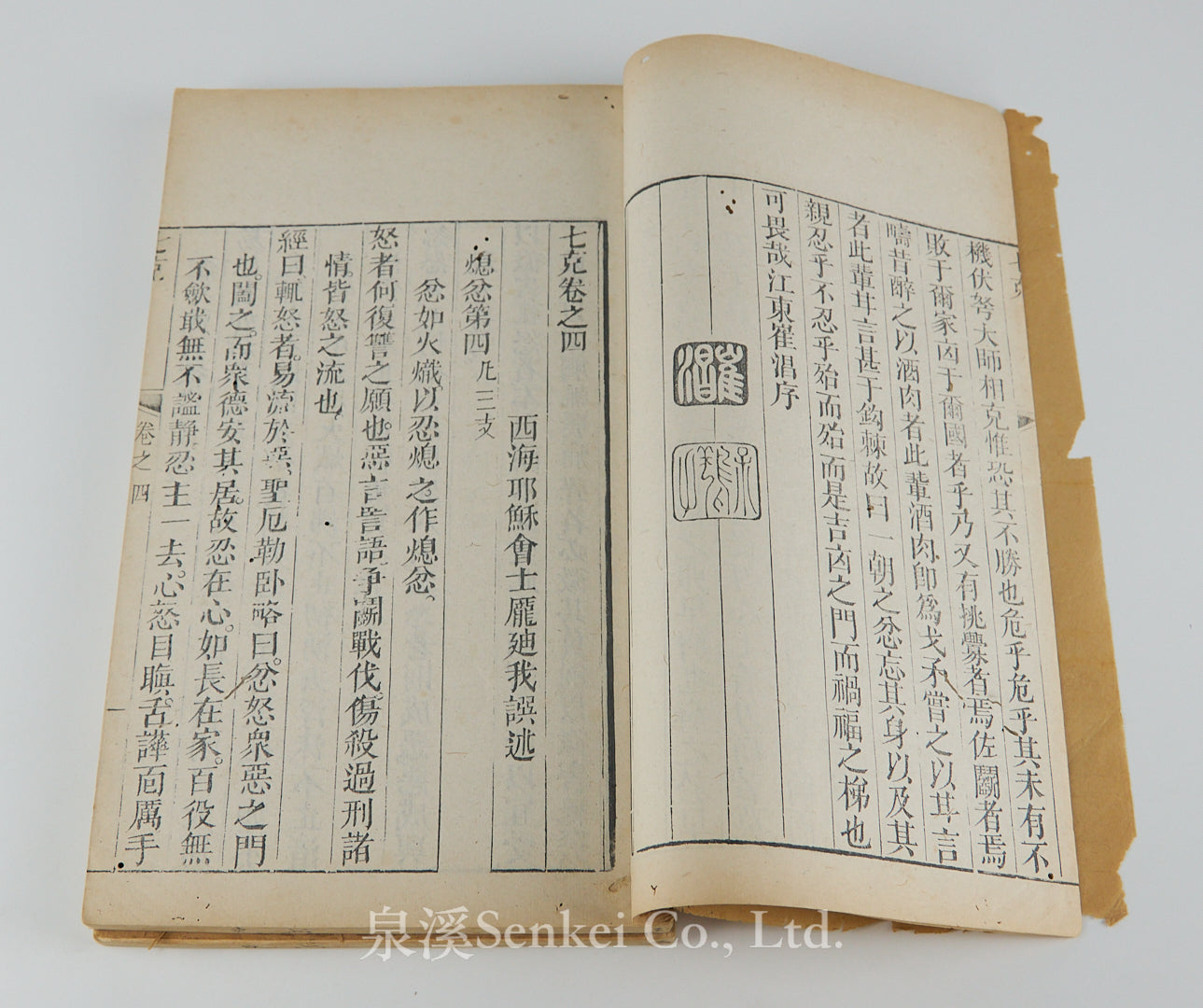

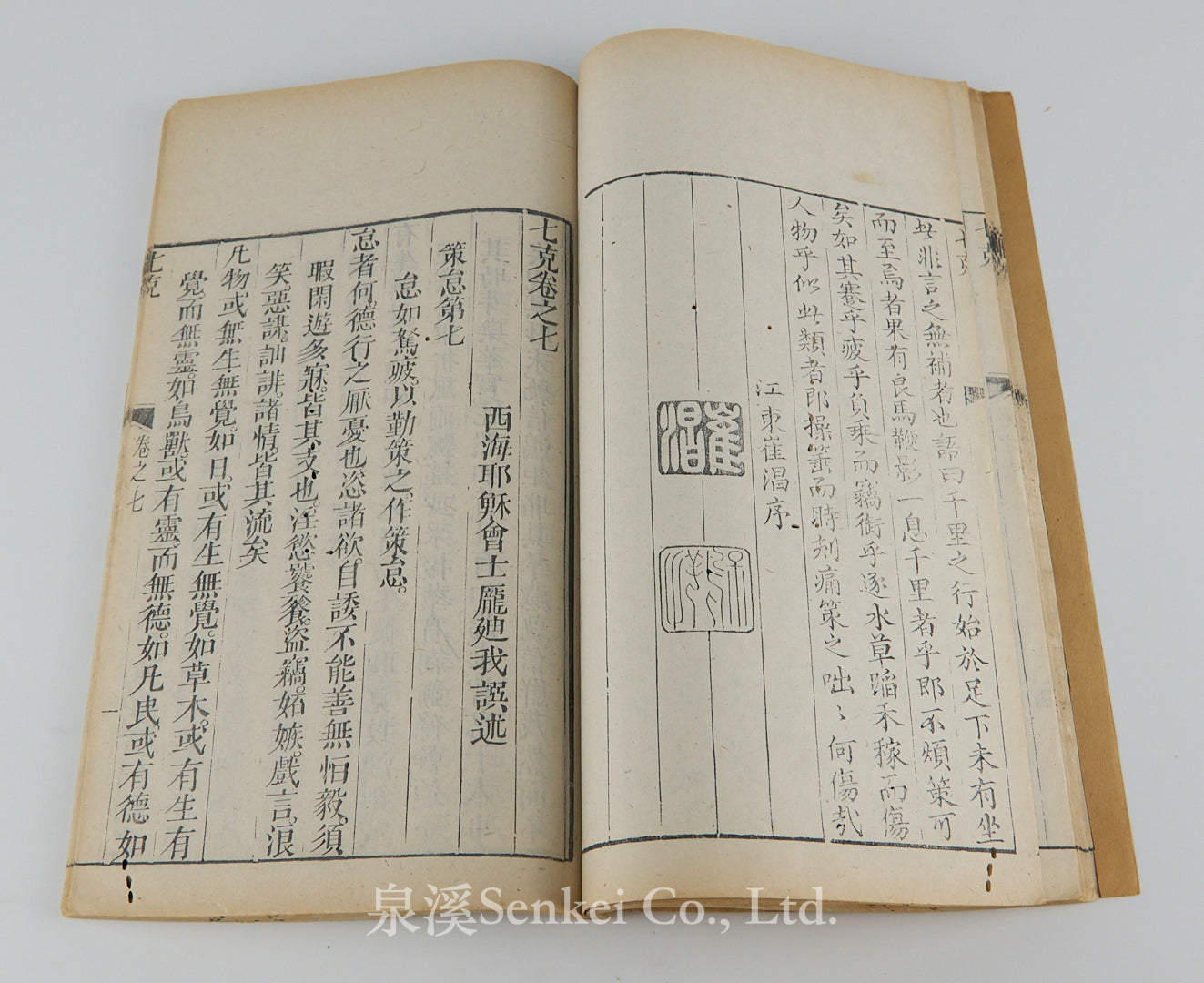

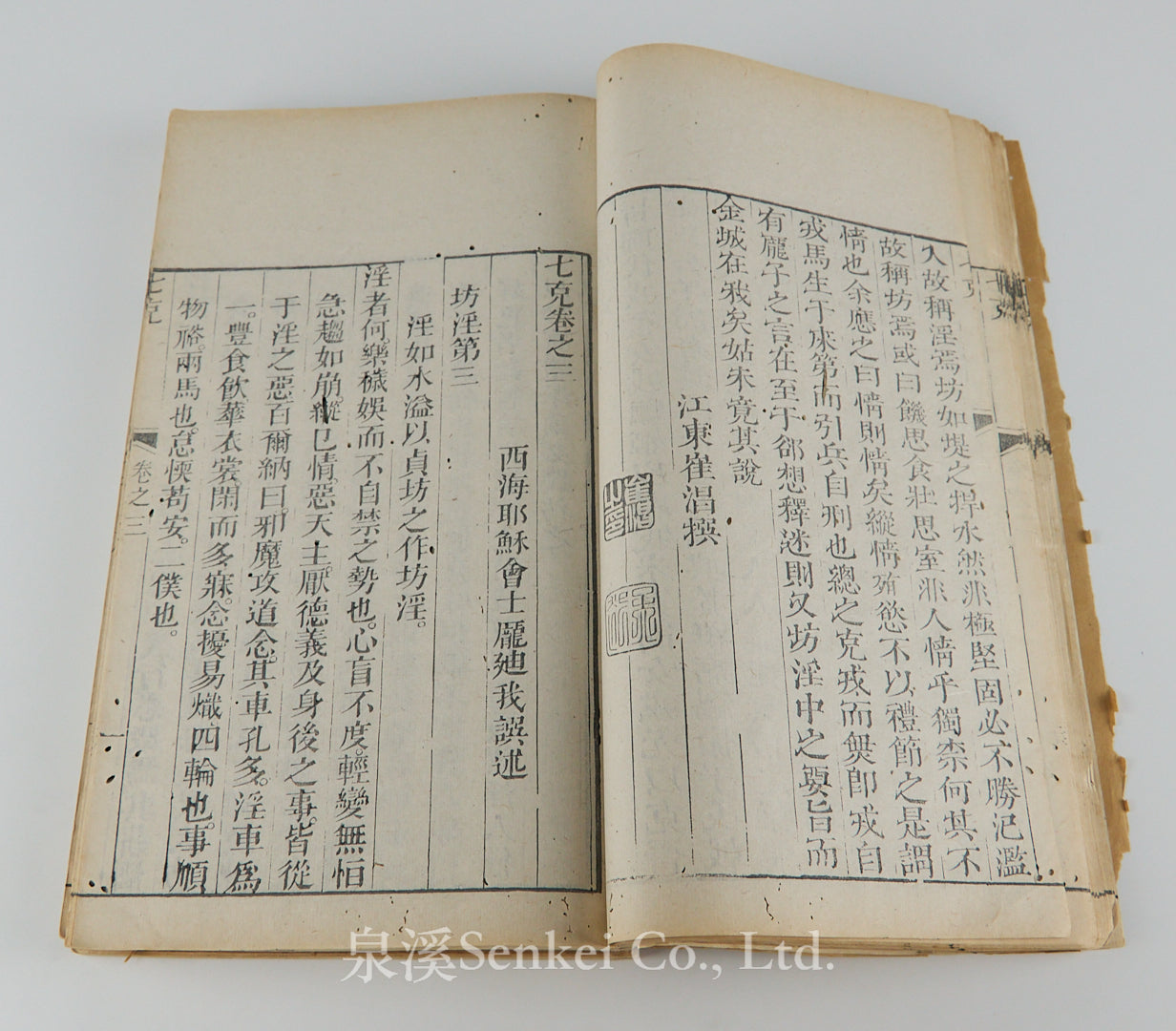

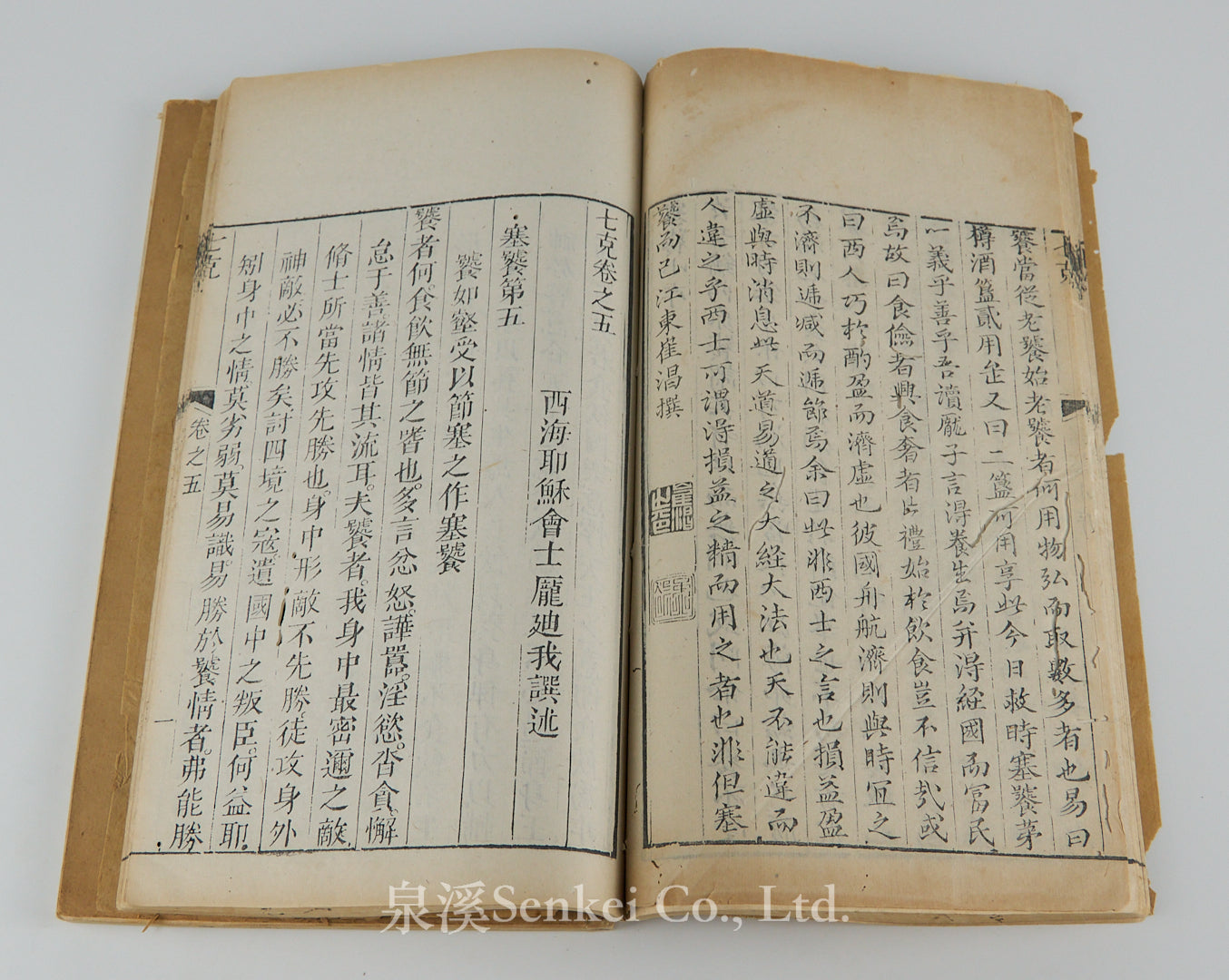

QI Ke | Septem Victoriis by Spanish Jesuit Diego de Pantoja (庞迪我) 1798/The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Peking 4 volumes

QI Ke | Septem Victoriis by Spanish Jesuit Diego de Pantoja (庞迪我) 1798/The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Peking 4 volumes

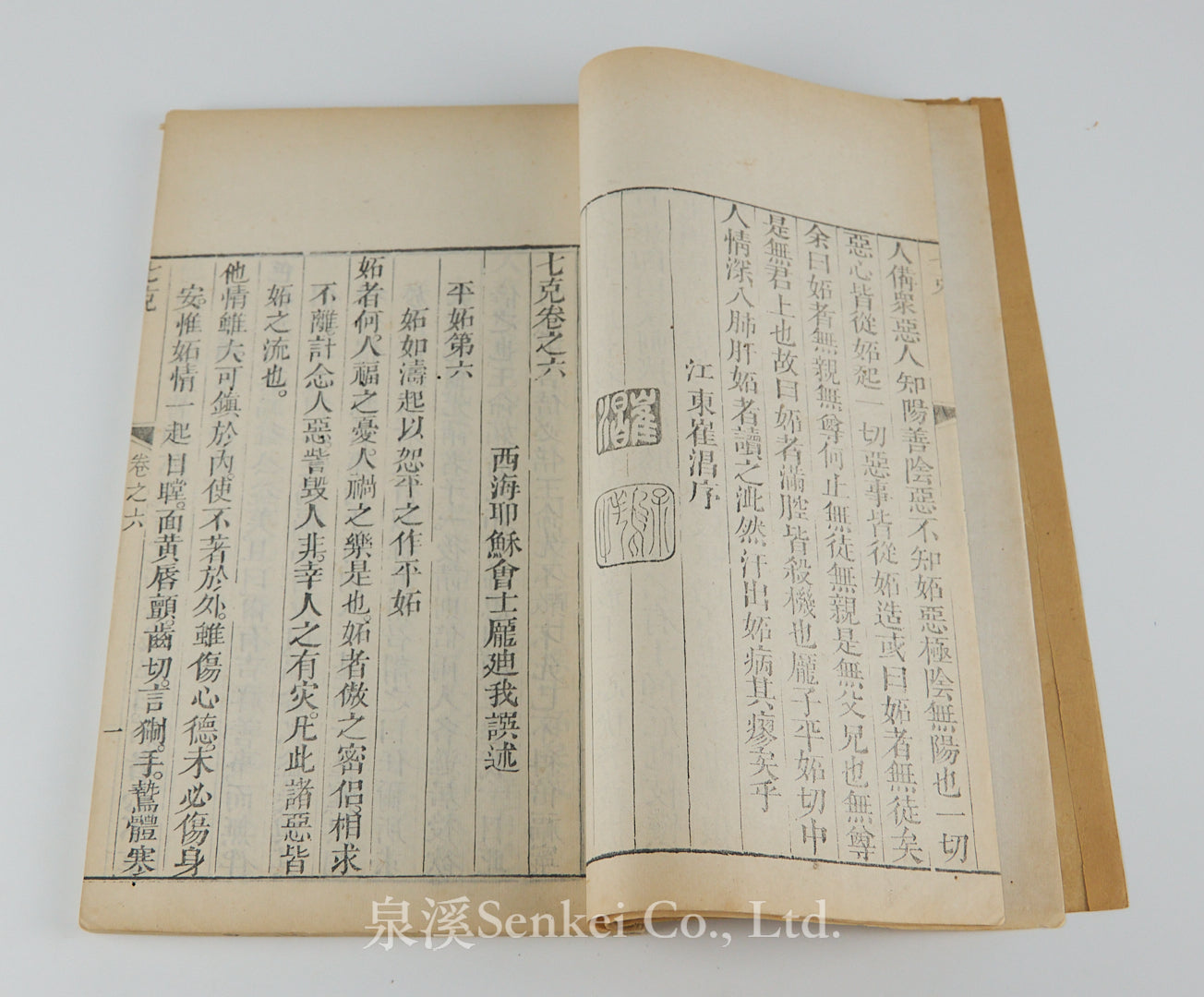

1798年《七克》耶穌會西班牙傳教士庞迪我著/京都始胎大堂藏版

作者(Author):Diego de Pantoja 庞迪我

出版社(Publisher):京都始胎大堂 The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Peking

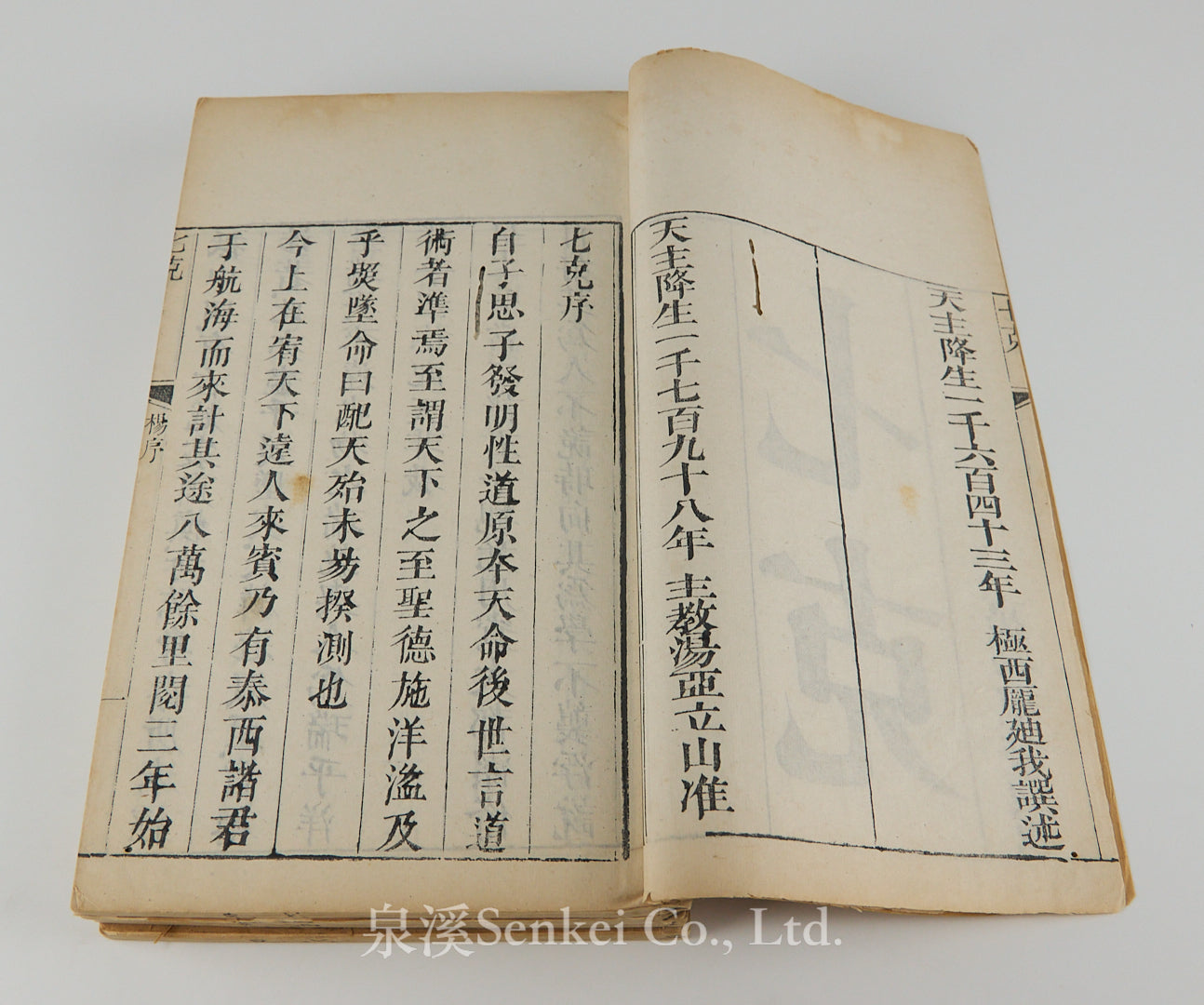

出版時間(Publishing Date):1798

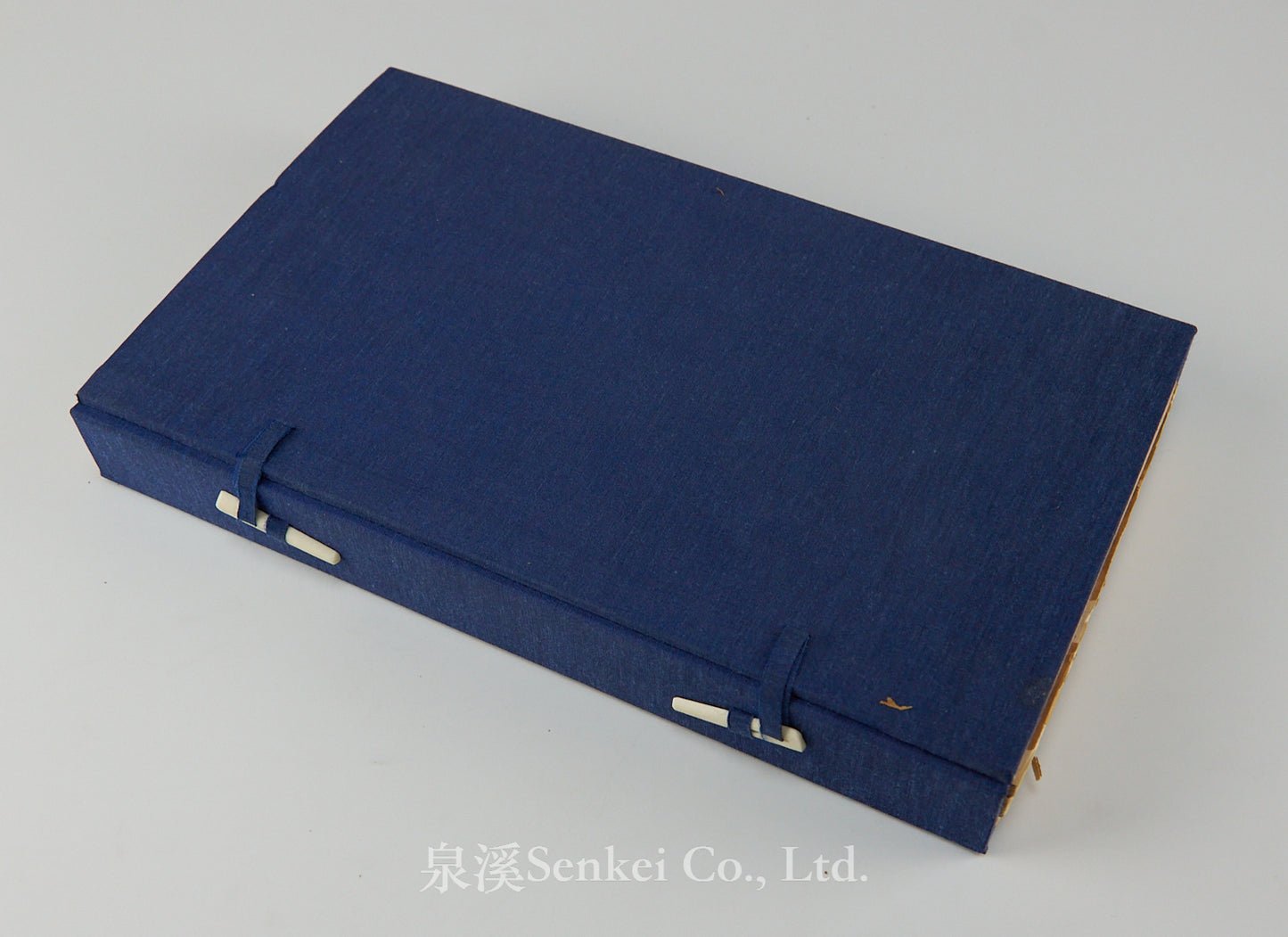

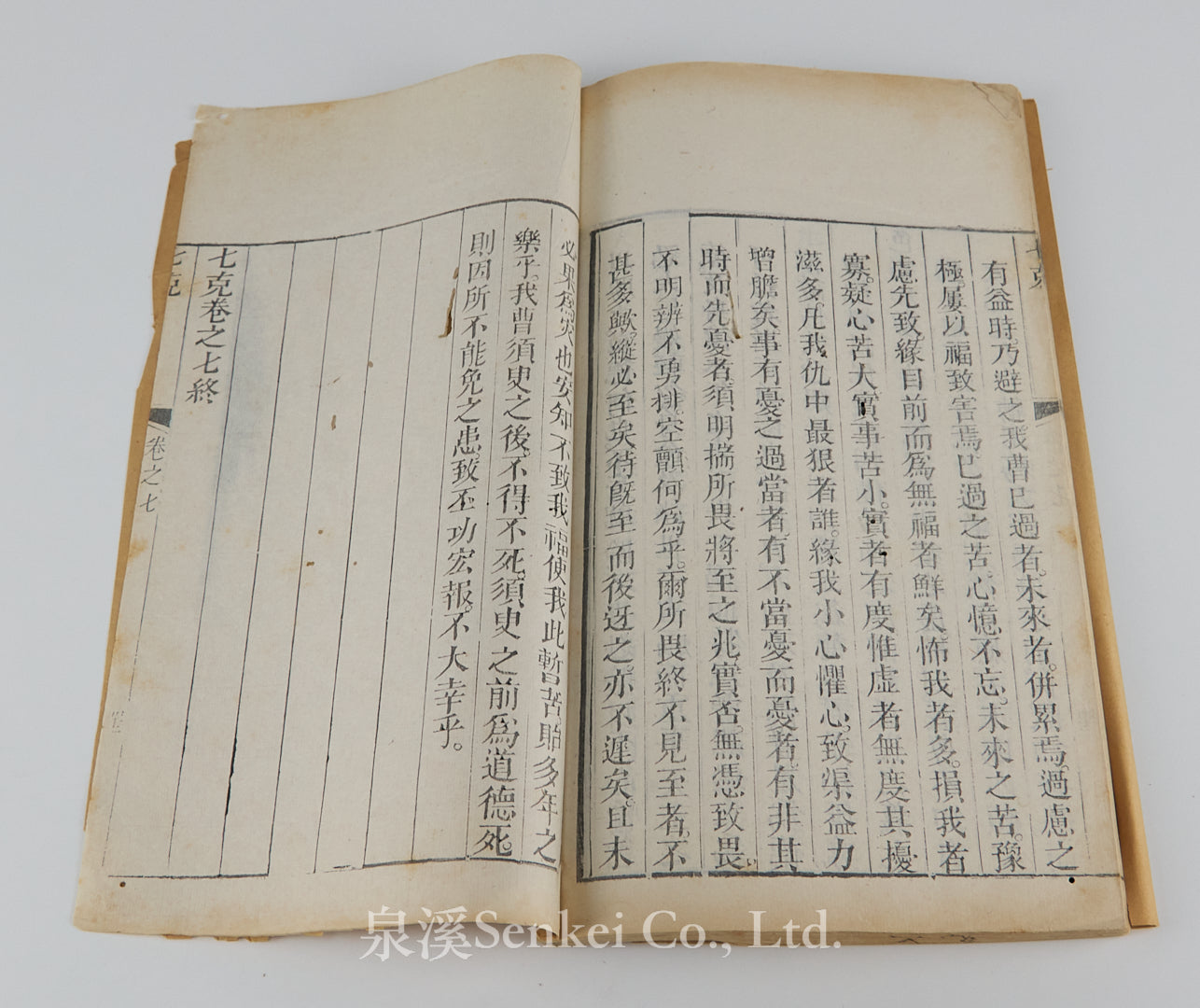

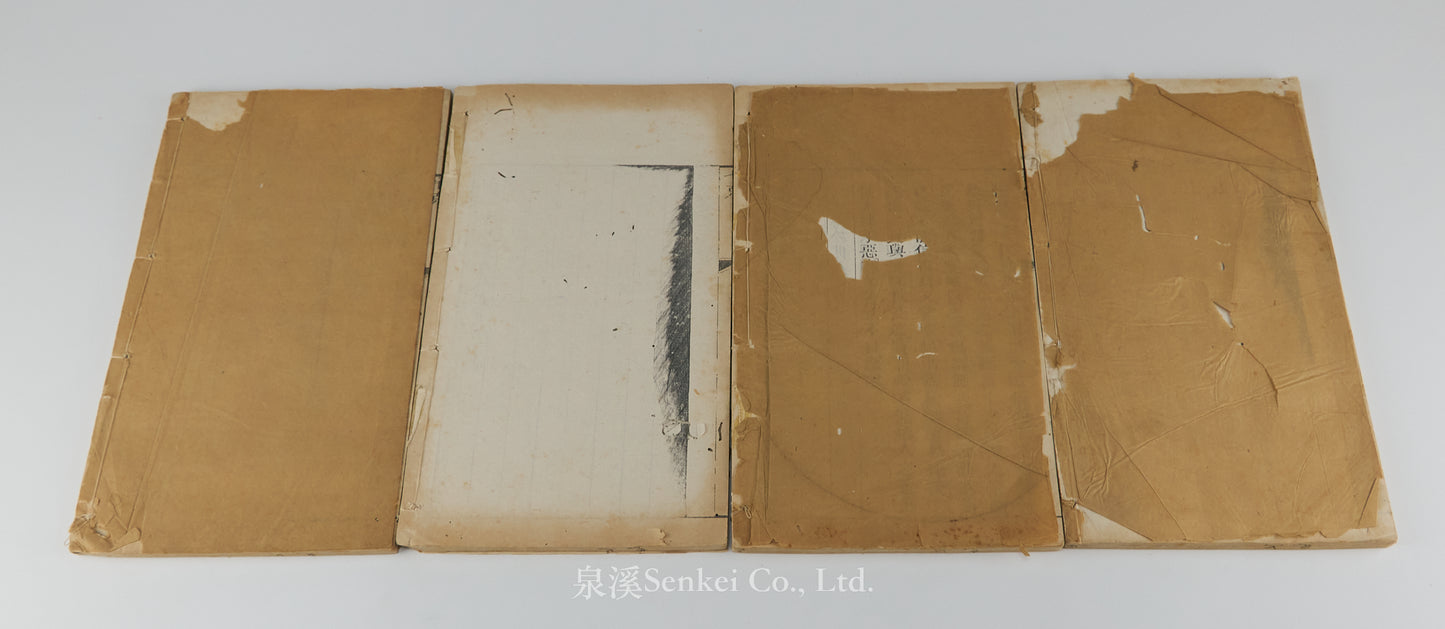

裝幀(Binding): Thread-bound

品相(Condition):Good 八品

尺寸(Size):26.5x16.5x3.5cm

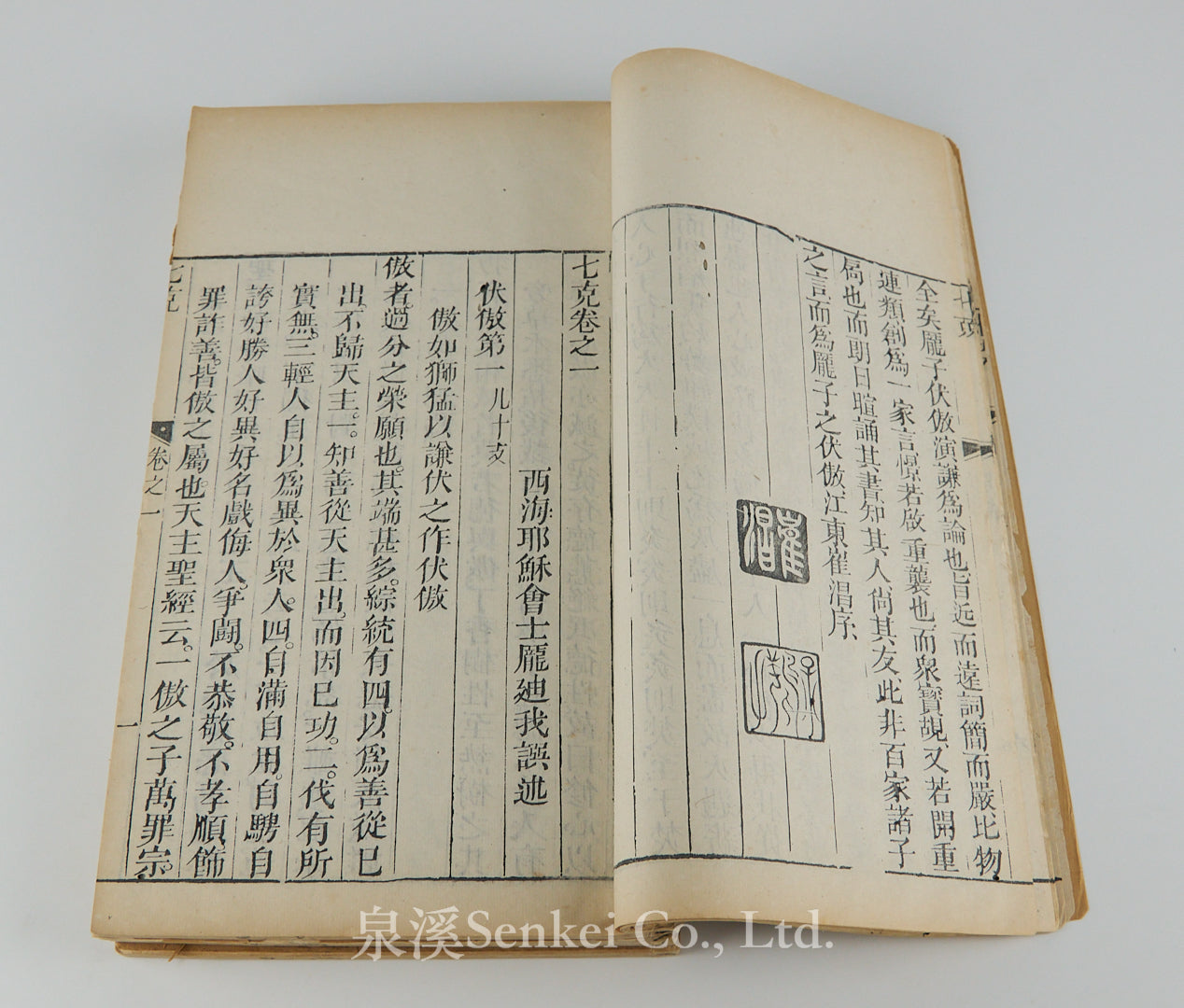

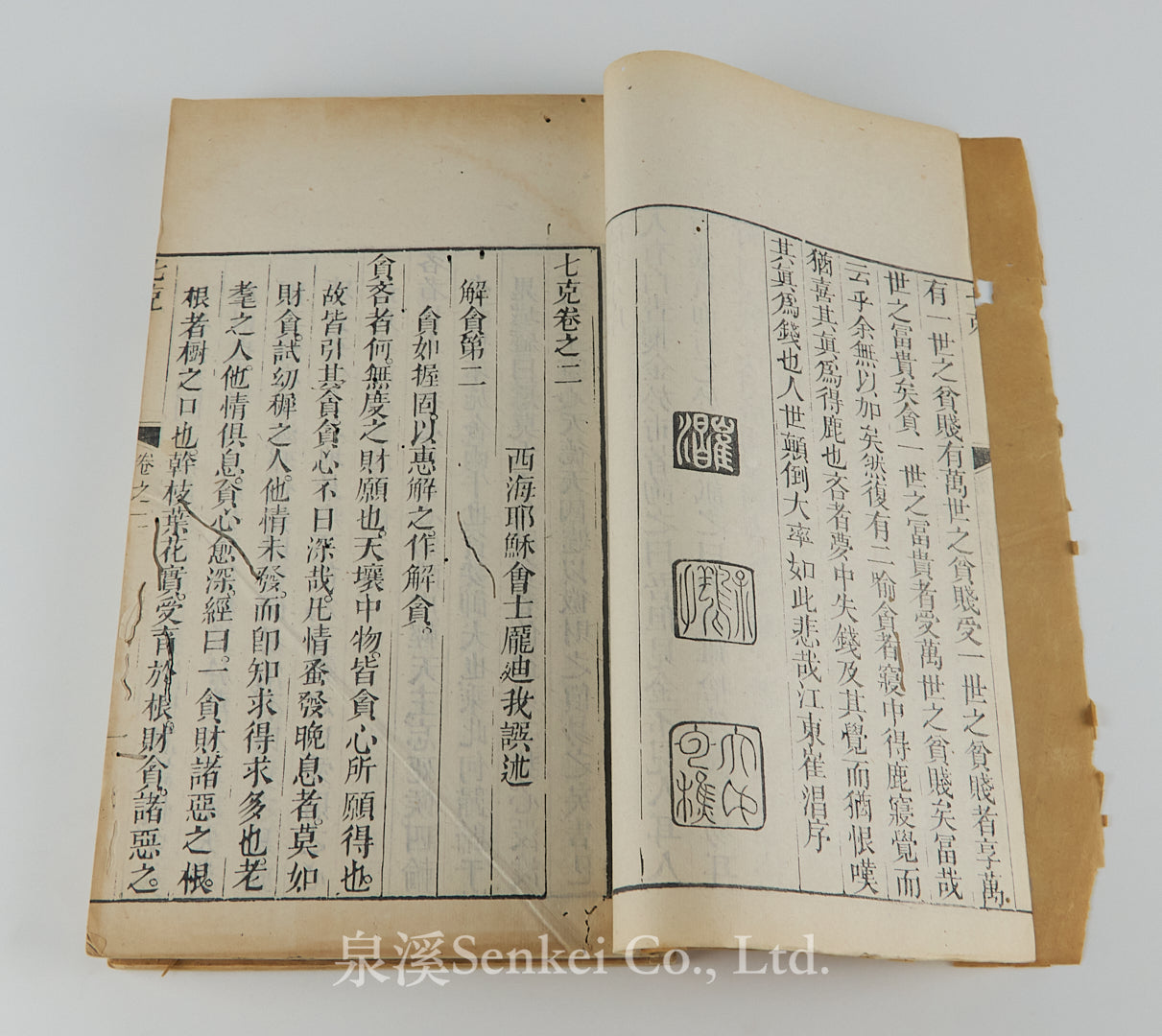

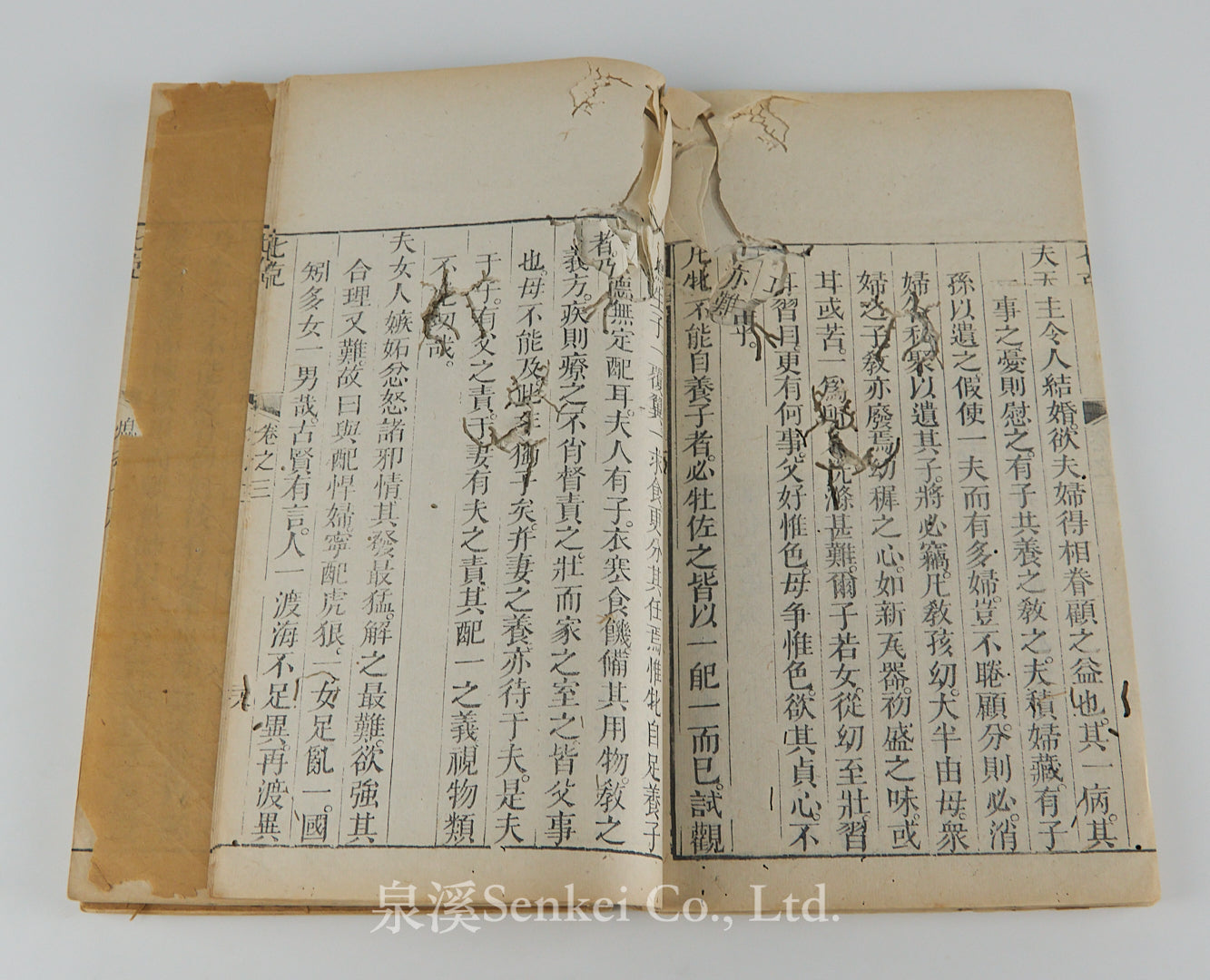

Slight damage to covers; back cover missing from the second volume. Worming, especially in the second volume, with around ten leaves more seriously damaged. One page in the preface of the first volume is misbound, but the set is complete with no missing pages.

Pang Diwo (the Chinese name of Diego de Pantoja, 1571–1618) was one of the closest collaborators of the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci. After Ricci’s death in 1610, only three Jesuit missionaries remained in China: Nicolò Longobardi (1566–1654/55), Sabatino de Ursis (1575–1620), and Pantoja. Having arrived in Beijing with Ricci in 1601 as his assistant, Pantoja followed Ricci’s approach of engaging with Chinese scholars and officials, promoting Western knowledge, and discussing Christianity in dialogue with Confucianism. Like Ricci, Pantoja contributed significantly to the introduction of Western science and cartography to China. Between 1583 and 1610, Pantoja and his fellow missionaries interacted with at least 137 high- and mid-ranking Chinese officials, several of whom converted to Christianity.

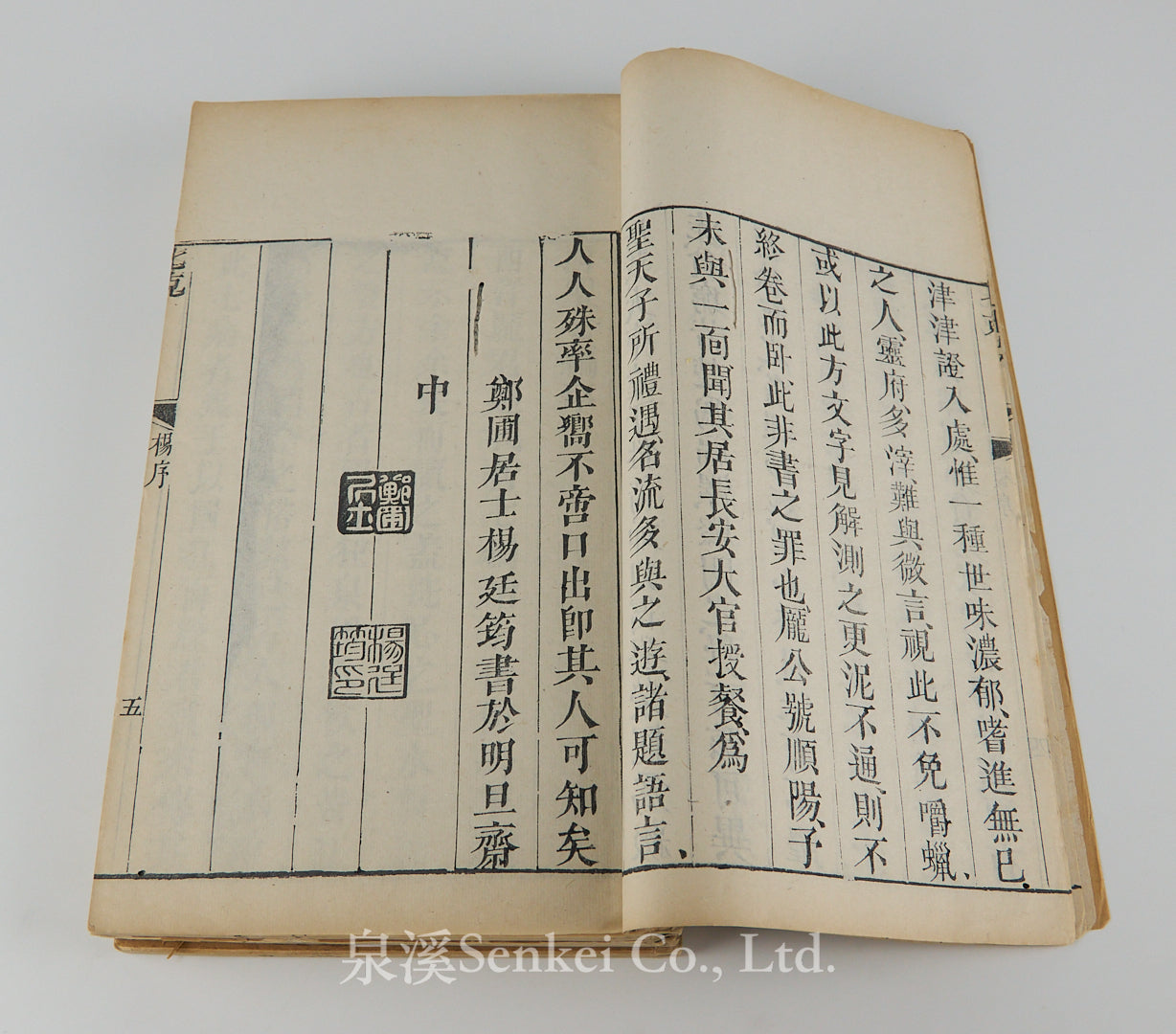

Due to growing tensions between the missionaries and the Chinese imperial authorities, Pantoja was expelled from China in 1617 and died in Macau at the age of 47. The Jesuit mission in China was supported by prominent Chinese literati and officials such as Xu Guangqi, Li Zhizao, and Yang Tingjun (1557–1627).

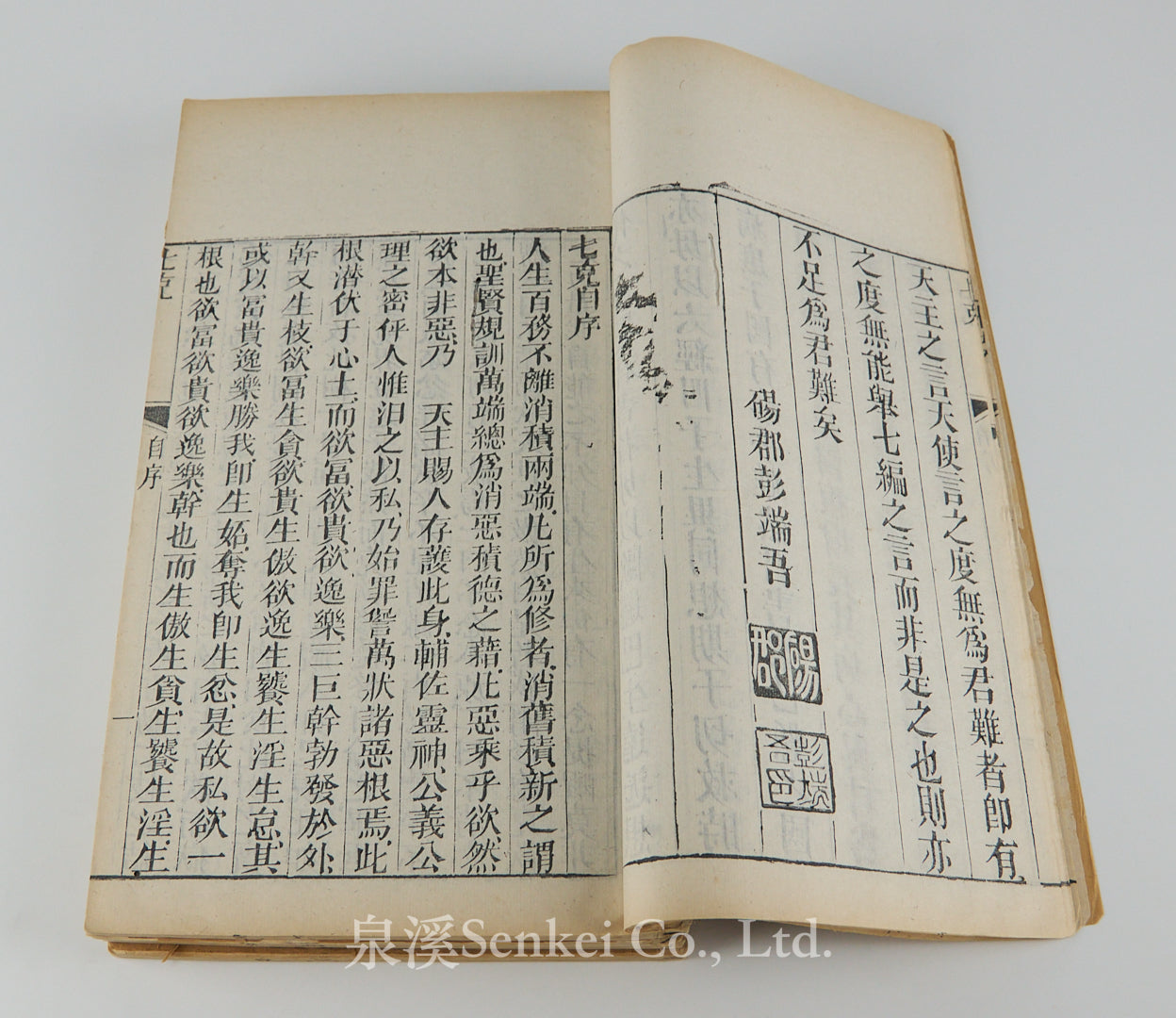

Qi Ke is one of Pantoja’s representative works. It explains the seven deadly sins of Christianity—wrath, greed, sloth, pride, lust, envy, and gluttony—and the seven corresponding virtues—patience, charity, diligence, humility, chastity, kindness, and temperance—drawing parallels with Confucian ethics such as benevolence and reverence. While aligning Christian morals with Confucian ideals, Pantoja also criticized Buddhist beliefs such as reincarnation. The work was reviewed and edited by Chinese collaborators, including Yang Tingjun, Peng Dewu, and Cui Chang, whose prefaces reflect the strong cooperation between Pantoja and Chinese literati.

Source: Library of Congress, loc.gov

Ask a Question